Congress and the power to declare war

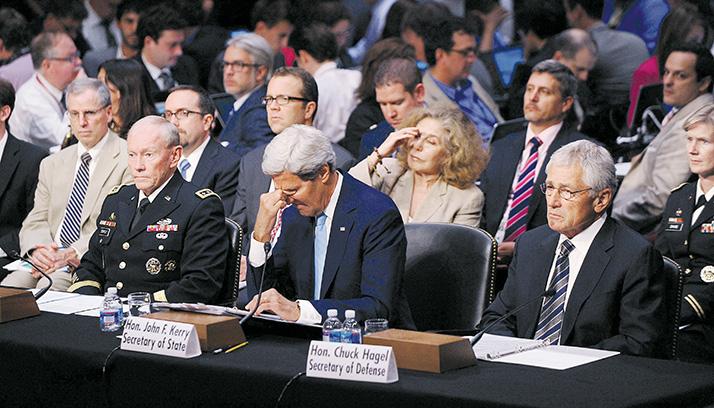

Photo by Olivier Douliery/Abaca Press/MCT

Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff General Martin Dempsey (left), Secretary of State John Kerry and Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel testify at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to argue the Obama administration’s case for using military force in Syria on Capitol Hill Sept. 3 in Washington, D.C.

As Congress considers authorizing punitive strikes against Syria, it can say yes, it can say no, but it better say something or it will forfeit its claim to war powers.

Most of the time since the passage of the 1973 War Powers Act, Congress has largely punted when presidents undertook major military operations. Members preferred to sit back, applauding successes and criticizing setbacks. Lawmakers complained about not being consulted, then voted for “support for the troops,” but they rarely reconciled their differences before sending a law to the White House.

No wonder most presidents have largely ignored Congress and its War Powers Act. There are strong arguments in favor of military action related to American credibility and revulsion against Syria’s apparent use of chemical weapons on innocent civilians.

There are also strong arguments against using force without the blessing of some international organization and in such a limited, symbolic way that is deliberately not intended to affect the outcome of the conflict in Syria.

Rather than viewing this debate as a chance to score political points, Congress should seize it as an opportunity to craft a broader policy on Syria. Decide how to respond to the chemical attacks, presumably with authorization for a limited reprisal raid. Decide what to do for the 2 million refugees who have fled the country.

Decide what kind of military aid and training to give which opposition factions. Give the president a consensus policy bill and pressure him to carry it out. Chances are that a majority in Congress do not want a large-scale U.S. military intervention, at least under current circumstances. Even the strongest hawks say they oppose U.S. “boots on the ground.” OK. Write those limitations into the law and insist that the president follow them.

Vote the money for aid to our allies. And accept responsibility for the consequences. U.S. history provides a broad menu of options for dealing with presidential requests for an authorization of force. In five conflicts, Congress voted to declare war. That formula hasn’t been followed since World War II, however, because lawmakers didn’t want to trigger the vast array of domestic laws giving the president enormous control over the economy and calling into question the validity of contracts and insurance that come into force when the “W-word” is used.

On 16 other occasions, Congress authorized the use of force but didn’t formally declare war. On at least six recent occasions, Congress took votes but never sent laws to the president supporting or opposing major military operations in Grenada, Panama, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo. On several occasions, Congress was asked to approve military actions and refused. In 1812, lawmakers defeated a bill sought by President James Madison to occupy and establish a government in eastern Florida. President James Buchanan twice in 1858 and 1859 asked Congress for the authority to send troops into northern Mexico and establish a protectorate there because of widespread civil conflict and atrocities against Americans. He never sent the troops because the Senate first defeated such a bill and then failed to act on his second request.

In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked for authority to arm merchant ships to deal with unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany, and a small group of senators successfully filibustered the bill. Three weeks later, the Senate for the first time adopted a rule allowing two-thirds of the members to cut off debate and, soon after, declared war on Germany.

Congress also has specifically banned certain military operations favored by the president. Lawmakers prohibited sending U.S. ground troops into Laos or Thailand in 1969. They banned aid or military activities in Angola in 1976 and in Nicaragua in the 1980s.

Sometimes Congress has set conditions on military involvement. In 1898, Congress declared war against Spain to liberate Cuba, but it ruled out annexation of the island, largely because U.S. sugar interests didn’t want the competition. In 1983, Congress approved U.S. participation in a U.N. peacekeeping operation in Lebanon, but it insisted that the mission be defensive and not take sides in the Lebanese civil war.

In 2001, Congress rejected the blank-check language to fight terrorism proposed by the Bush administration and limited the authorization of force to only those connected to the 9/11 attacks. If lawmakers really care about Congress’ war powers under the Constitution, they should step up to the plate now.