When I look through the kitchen window and see icicles melting, I know it’s getting warmer outside. The ice serves as a kind of thermometer, signaling temperature change. So it is with Mother Earth. The decline and retreat of our home planet’s ice – the cryosphere – documents global warming just as surely as a medical thermometer reveals a fever.

Earth’s ice is stored in the cold climatic zones of high altitude and high latitude. But now geologically “instantaneous” human-caused warming is abruptly disturbing cryosphere equilibrium so that the rate of ice loss (negative mass balance) and consequent impacts are accelerating.

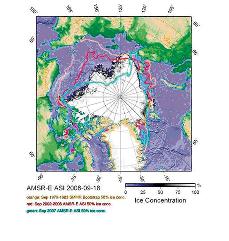

The cryosphere comprises sea ice, glaciers, and frozen lakes, rivers and ground (permafrost). All of these components change with the seasons to some extent, increasing in the winter and decreasing during summer.

The larger and insulated ice masses, such as glaciers and permafrost, fluctuate little or not at all with the seasons, whereas relatively thin sea ice and frozen lakes and rivers disappear and reappear annually.

It is the longer trends, however, that reveal climate change. And almost all components of the cryosphere experience accelerating, long-term meltdown: ice sheets and outlet glaciers, ice caps and mountain glaciers, ice shelves and sea ice, and permanently frozen ground.

This worldwide decline not only documents changing climate, it forewarns humanity of potentially catastrophic impacts on water supplies and coastlines.

Shrinking glaciers in the planet’s great mountain belts threaten diminished discharge to major river systems and reduced recharge to aquifers upon which extensive agriculture and vast populations depend.

Rising sea levels resulting from thermal expansion and melting glaciers put many of the world’s coastal areas at ever-increasing risk of flooding and reconfiguration by storms. Low-lying lands on deltas and atolls are especially vulnerable.

Albedo and other positive feedbacks are driving the most rapid melting in the polar regions: the Arctic, including Greenland, and the Antarctic, particularly the Antarctic Peninsula.

When highly reflective snow and ice disappear, the newly uncovered land and water surfaces are much darker and absorb much more heat. This in turn accelerates warming and ice loss thereby producing a positive feedback or “vicious circle.” As a result, the average temperature in the Arctic has increased some three to seven degrees Fahrenheit in just the past half century.

Loss of summer sea ice not only challenges the traditional way of life of indigenous peoples in the Arctic, it threatens the survival of Arctic mammals such as polar bears, seals and walrus. These animals depend on sea ice for hunting, protection and nurturing of their young.

How shall we respond to these warning signals from our planetary thermometer?

What must we do to keep this accelerating crisis from becoming a runaway catastrophe later this century? We already know the answer – drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions! Will we do it? (To be continued.)