It’s a bright spring day. Children are out riding their bicycles in their picture-perfect subdivision while their parents tend to already-tidy lawns. Young boys fish on the riverbed in a rolling green park. Others are walking their dogs and stopping to chat with neighbors. Down the street, a family sits on a park bench enjoying a treat from the town’s favorite local ice cream shop.

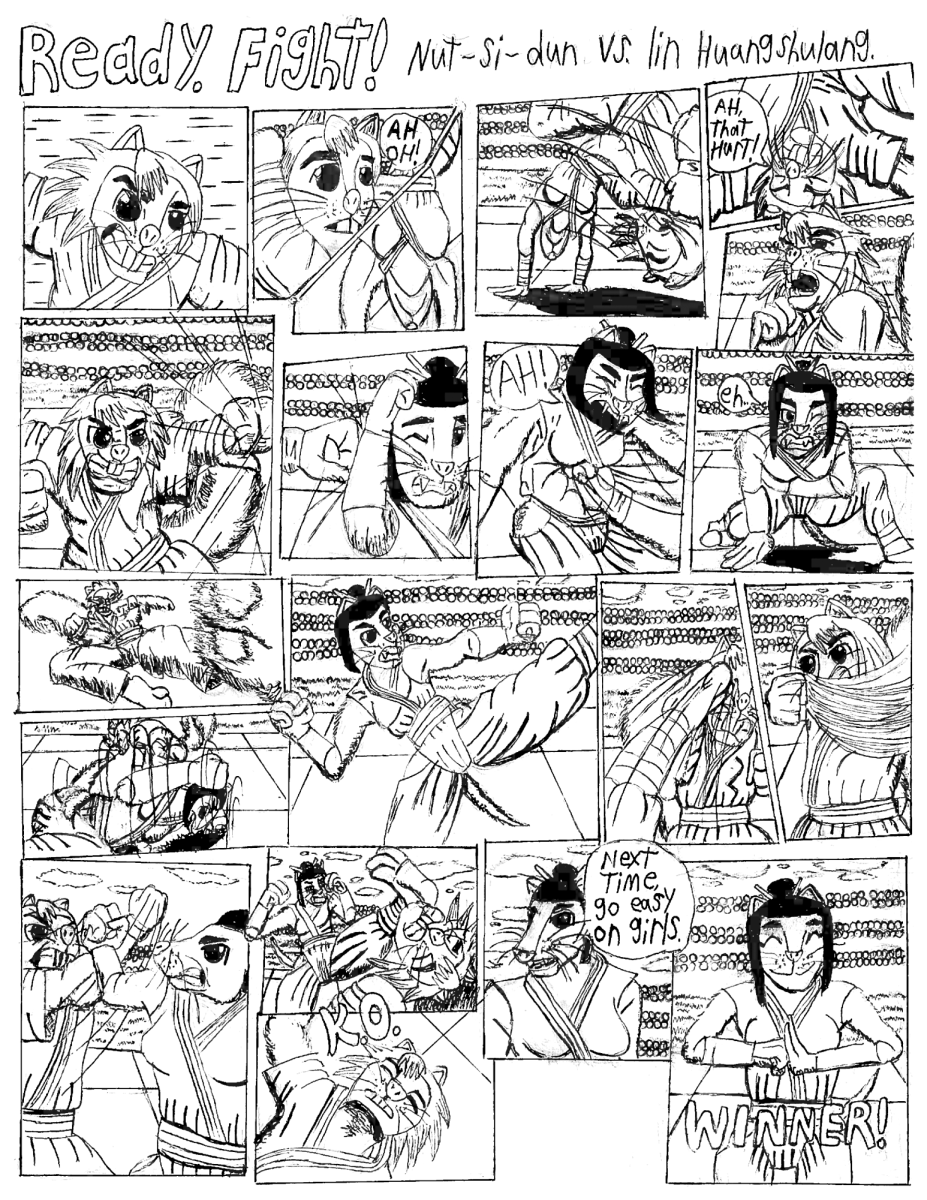

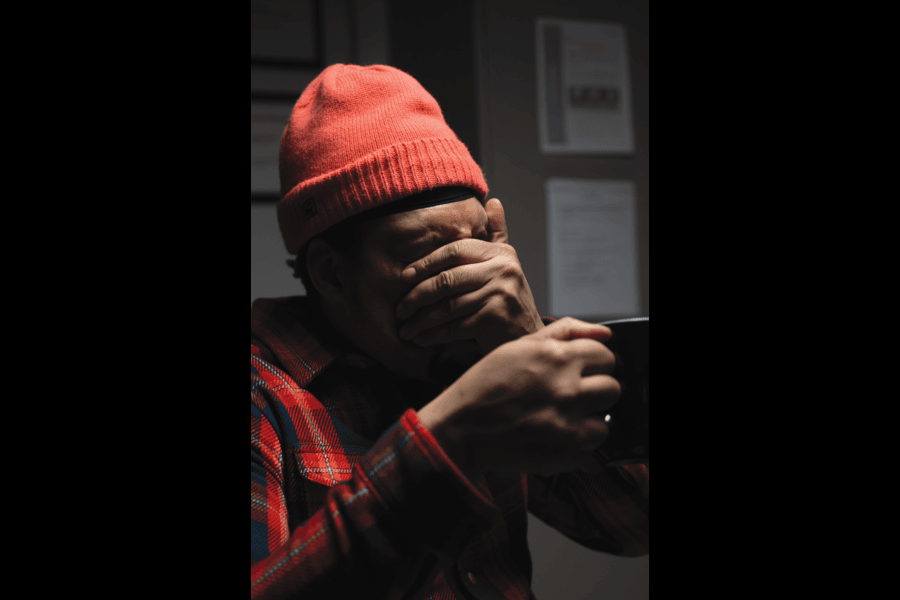

Not 25 miles away a very different scene unfolds. Abandoned houses sit in weed-filled yards, decorated with the broken glass of liquor bottles. Young men sit in a car parked on the street passing a blunt.

A teen mother rushes across the street with her son. A billboard encouraging HIV testing stands overhead. Garbage clings to chain link fences. Metal bars adorn corner stores and boarded up businesses are decorated in graffiti. Ambulance and police sirens wail. People sit, somberly waiting for the bus.

Which place would you rather raise a child?

For many Milwaukee inner-city blacks there is no choice. They do not have the means to escape this environment of desolation. Disparity is prevalent here and the differences are immense.

Recently, Milwaukee was voted the third top worst city in the nation for blacks to live. The report, released by www.blackagenda.com was primarily based upon Milwaukee’s high incarceration rates of blacks. According to the report Wisconsin African-Americans were incarcerated at a rate more than six times that of whites. A staggering percentage considering that blacks make up no more than 6% of Wisconsin’s entire population.

As time progresses, only more daunting statistics are unveiled. Of the nearly 2,000 homeless persons living in Milwaukee, 68% are black.

As of press time, out of the 23 persons murdered so far this year, 14 were African-American. Most of the victims were murdered by other Milwaukee blacks. Last year the number of homicides reached 105. Again, most of the perpetrators and their victims were black.

In a recent Milwaukee Journal Sentinel report by Alan J. Borsuk, the National Assessment of Educational Progress found that Milwaukee’s African-American fourth and eighth graders ranked the lowest in the nation in average reading and writing scores. In his article, Borsuk states that “something is seriously off course in the education of African-American children in the state.” This is only further proved when one learns of the dismal graduation rate of African-Americans (46%) enrolled in Milwaukee’s Public School system. On the college level, Milwaukee is home to the fewest of black college graduates in the country.

Milwaukee also has the nation’s highest teen pregnancy rate. Nationally, two out of three African-American mothers are single mothers. With each new single mother, frightening statistics follow. Without a father in the home and with the mother usually working, children of single mothers are at an alarming risk of committing theft, joining gangs, abusing drugs and alcohol, selling drugs, becoming pregnant or being involved in violent acts.

In addition to the aforementioned, African-Americans in Milwaukee also have the country’s lowest home ownership rate.

Is it safe to say that Milwaukee African-Americans are in

crisis?

Milwaukee Sheriff David Clarke thinks so. “Without a doubt, it is in a crisis stage. The black income level, low levels of home ownership, high crime rates and a failing public school system are all serious risk factors.” He also cited, “the middle class flight” (middle class blacks who flee to the suburbs) as reasons for the emergence of what he called “the underclass.”

When asked whether high crime rates had also risen amongst other demographics, Sheriff Clarke said they had not.

Some Milwaukee residents blame the recent spike in crime, violence and other problems occurring in the community on Milwaukee’s pertinent segregation.

They believe that the resulting disparities between the whites and blacks of the city stem from disproportionate opportunities.

Although the six members of MATC’s Black Student Union interviewed refuted the idea that these problems are to blame on “the man,” (the white man), they still felt that blacks were treated unfairly. Miquel Davis said, “Society is so judgmental.

Second chances are not given. Sometimes I think it’s all a trap.” Vanidy Perkins, also of BSU, believes unfair portrayal in local media is additionally to blame.

Part of the problem, they explained, is that there is a lack of leadership within these neighborhoods. “It’s not like the ’50s and ’60s where we had people speaking for black people, lobbying for what is important,” said Samson Ray, president of BSU.

“We need somebody who has influence in the community to step up.” He adds that across Milwaukee there is a lack of unanimity in the community, that there is no longer that sense of “neighborhood watch.”

Sheriff Clarke believes it is this lack of unity, a lack of political leadership and a lack of political commitment that have allowed for others (such as gang members and drug dealers) to take over and intimidate neighborhood residents. But he does not blame the residents of this community.

Instead, he believes that the police and local law enforcement have done an “inadequate job of connecting with residents. There is absolutely no relationship.”

“There is a whole lot of distrust with the police,” said Davis. “They don’t provide security for us.”

Without this trust people fear turning in violators of the law, which only gives more power to those breaking it. Additionally, a covert commitment to not “snitching” has been deeply instilled in these communities.

Without the support of local law enforcement and politicians, lack of unity within the community, inadequate education, unstable families and the demoralization of values, Milwaukee can expect to see these high rates of crime and violence become more than just a recent “trend.”

Leaders and residents in the community need to stand up and begin to defy the negative stereotypes of African-Americans before these problems begin to become real definitions of what it means to be black.