College no guarantee of American Dream

Photo by Kirsten Schmitt

Why are the hallways so empty?

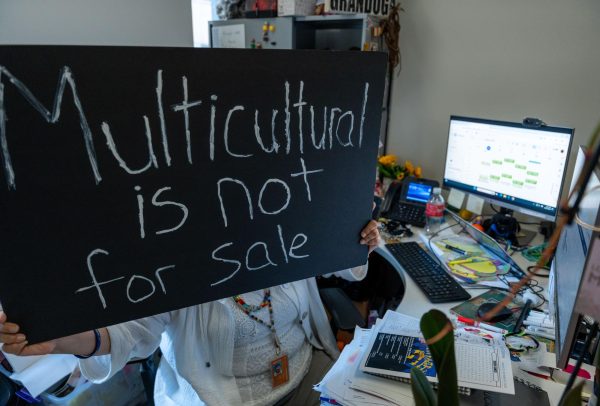

From the opinionated logical side of things, the dynamics of a proper education, in many cases, have over promised and under delivered; blanketing fancy names over saturated degrees, offering hopeful statistics of high- paying jobs, while being sold the must- have American Dream.

For most, the college investment decision involves the long run because the gains of higher education are presumed to accrue over time. In many cases it appears that a college education is merely used as a tactful screening device by employers to wean out potential, mediocre underachievers that lack charisma. The reality is these ambitious dreamers who actively pursue degrees in hopes of gaining financial security may never obtain employment in their preferred industry. A two- to eight-year or more commitment with no promise for return on investment; with a guaranteed price tag.

I’m certain there are many reasons that attribute to lower college enrollment, but my outlook concludes a strong presence of fear and finance. The truth is many prospects have done an exceptional amount of research. Opting out of taking a “chance,” appreciating and highly considering the power in numbers. Two-fifths of adult Americans have associate degrees or more, although less than a fraction of actual jobs are in the technical, professional or managerial fields that historically have been the vocational home for new college graduates. Gauging the lifetime earning potential versus time spent and money invested has been perceived as a “gamble.” Our economy’s current state and recent forecast of low- paying jobs requiring a high level of competency with vast competition can lead to a weary and discouraged potential college student.

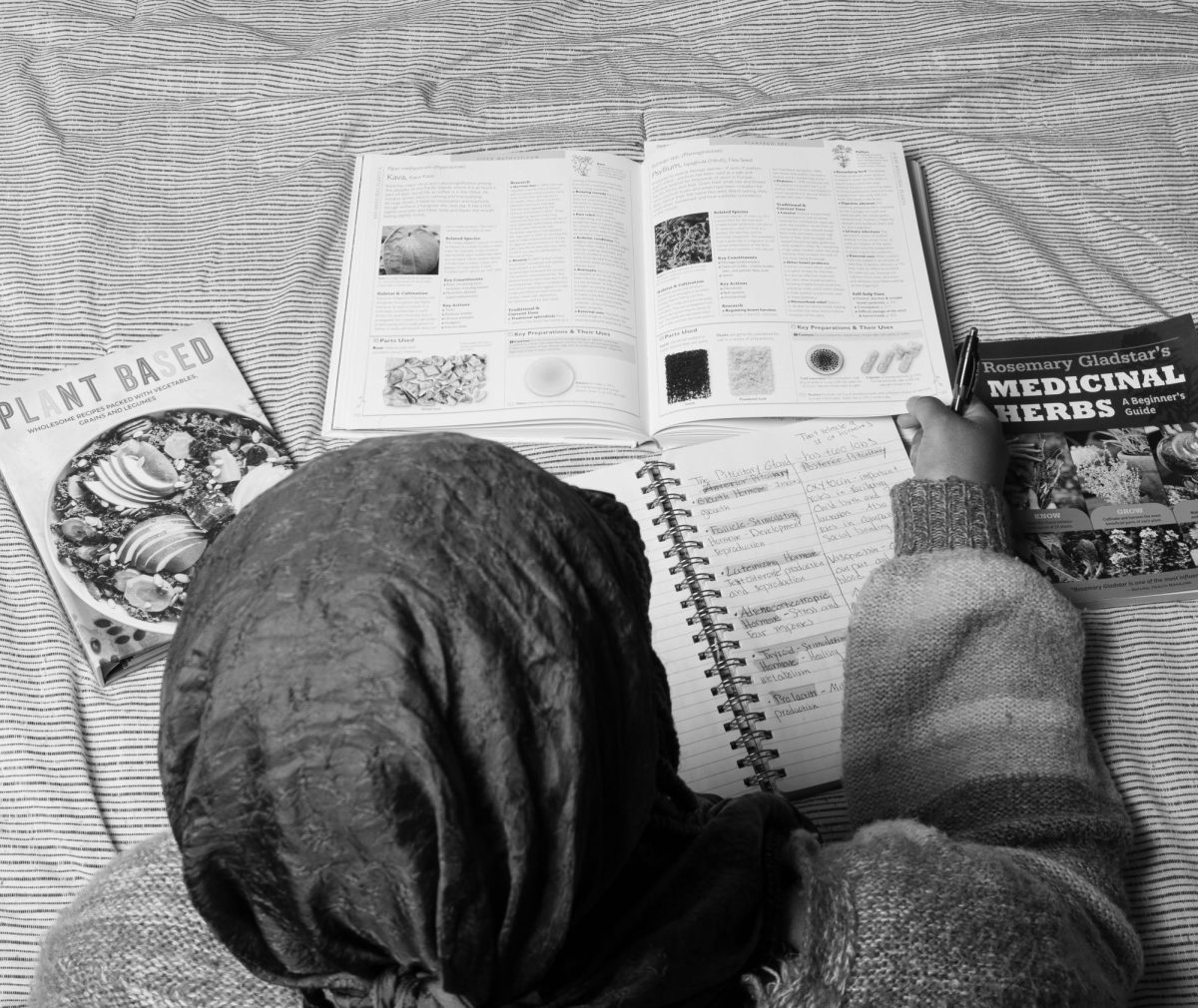

College institutions have also raised tuition costs that have encouraged a broader audience of skeptics. In my own words I ask, “Is it really worth it?” I won’t be sold a dream and upon enrolling as an Interior Design student, I was confident in my decision. Aware of the pros and cons of merely obtaining an associate degree, my “why” was, and still is more meaningful than a repayment plan. I refuse to manifest negative thoughts that persuade my decision for the pursuit of excellence.

Of course I am not oblivious or naive to the fact that I have incurred a handsome bill and financial obligation during my college tenure. Although my desire to achieve an undoubted and priceless amount of self gratification is worth every moment at this juncture in my life.

On the technical side of things, according to the U.S. Census Bureau report released September 2104, college enrollment declined by close to half a million (463,000) between 2012 and 2013, marking the second year in a row that a drop of this magnitude has occurred. The cumulative two-year drop of 930,000 was larger than any college enrollment drop before the recent recession, according to U.S. Census Bureau statistics from the Current Population Survey. The Census Bureau began collecting data on college enrollment in this survey in 1966.

According to the new statistics, the drop in enrollment was equally divided between older and younger students. Enrollment of students 21 and younger fell by 261,000; the enrollment of students older than 25 fell by 247,000, not statistically different from the change in enrollment of students 21 and younger. Overall, 40 percent of those 18 to 24 were enrolled in college in fall 2013, after having reached 42 percent in 2011.

A large part of the decline took place in two-year colleges (known often as community or junior colleges). Such schools experienced a 10 percent decline in enrollment from 2012 to 2013, while enrollment at four-year colleges grew slightly (1 percent).

According to a Bloomberg News report, there are five possible reasons cited for dropping enrollments.

First, the population of 18-year-olds is in decline, and that is where most freshmen come from. Second, some admissions officials have been arguing that the turnaround of the economy is working to lower the numbers. When the economy tanks, young people and even older adults who are unable to get jobs head to college, and go back to work when the job situation improves. Third, eligibility for federal financial assistance has been tightened. For example, a Pell Grant recipient formerly could receive grants for nine — yes, nine — years; now the limit is six years. Believe it or not, a fair number (more than 100,000, according to Pauline Abernathy of the Institute for College Access and Success) of previous recipients of that money were cut off, possibly leading them to drop out of school. Fourth, colleges may in some cases be pricing themselves out of the market. Although full tuition-increase data aren’t available, it is virtually certain that this fall, tuition fees rose a good deal more than the rate of inflation.

In recent years, public school tuition fees have risen even more (largely because of stagnant state subsidies). Last and possibly most important, concern appears to be rising about the rate of return on college investments. One estimate is that as many as 53 percent of recent college graduates are either unemployed or have relatively low-paying, low-skilled jobs.

There is so much to think about and these facts can be hard to digest. It is so important in our fast-paced world and evolving societies that we make wise investments that will add value, and benefit us in our current and future endeavors.