Imagine the end of the world, not the preceding event that led to the end of the world, just what is left after the event. Fallout is a multimedia project including novels, an Amazon television series, and video game set in the imagined version of this world left in ruins by a nuclear apocalypse. People huddle together in bunkers created to sustain humanity in the event of one of these disasters and use crude remnants of society before the bomb to cobble together something new.

The series first two entries were roleplaying games viewed from a top-down perspective on the PC from the 1990’s, though it is most popular with modern audiences thanks to its third entry in 2008. Fallout 3 repositions the player’s perspective into the first-person and brings the player eye-level with the violence in the end of days. Since Fallout 3, the series has sustained popularity, and there is even a successful Massively Multiplayer Online iteration called Fallout 76 that has continued to receive updates to this day.

A good point of comparison for those unfamiliar with this series may be the Mad Max films; this genre of post apocalyptic fiction has long been a mainstay in cinema. It may manifest as nuclear apocalypse, natural disaster, zombies, or an AI uprising, but the results are the same, these films depict a version of humanity that is cruel to one another, squabbles over resources and engages in primal violence. It does make a lot of sense from a narrative perspective. In storytelling, violence is a shortcut to create compelling conflict, but the result is this codified public belief that when disaster strikes there will be chaos.

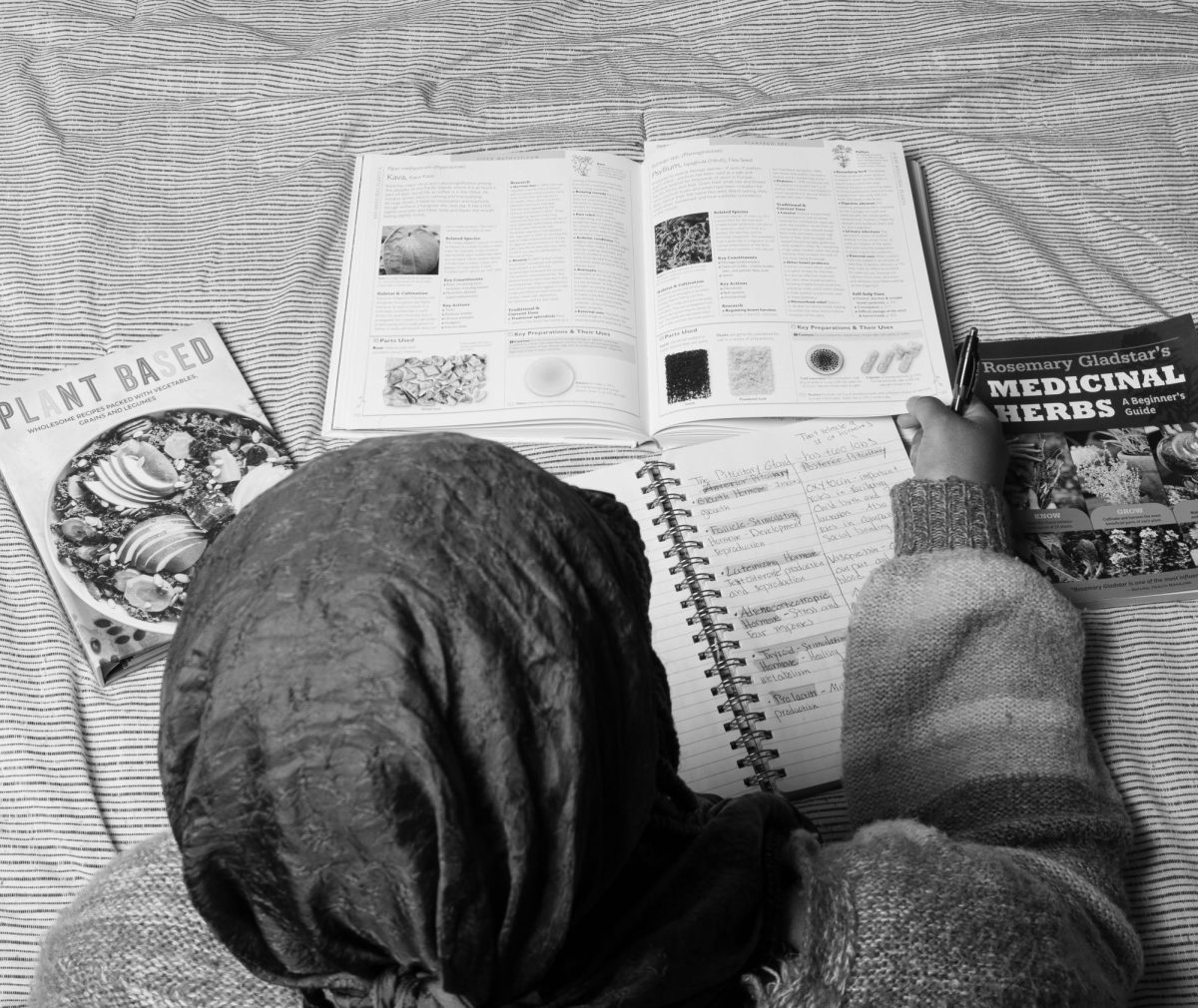

For this article, I read the book “A Paradise Built in Hell,” by Rebecca Solnit. In this book, she makes the case that over the history of recorded civilization natural disasters have not caused a breakdown in the social order, but rather they brought out the best in humanity. The book provides numerous hopeful examples, including the aftermath of a fire that devastated San Francisco where regular people gathered resources, served food and provided shelter to the people who were suddenly without.

Unfortunately, while a majority of people find themselves radically capable of great empathy not everyone participates. In 1985, an 8.0 magnitude shock leveled hundreds of buildings and killed over 5,000 people in Mexico City. When the people most needed help the government disappeared. Factory owners abandoned their workers and denied them their due pay. Police and soldiers were dispatched to provide protection to property and to stop looting, but government-sponsored rescue teams were nowhere to be found. In this vacuum of leadership, it was once again the regular people who came together to rescue families and neighbors, to feed and comfort each other. These brigades removed dangerous refuse and provided safe spaces to those in need.

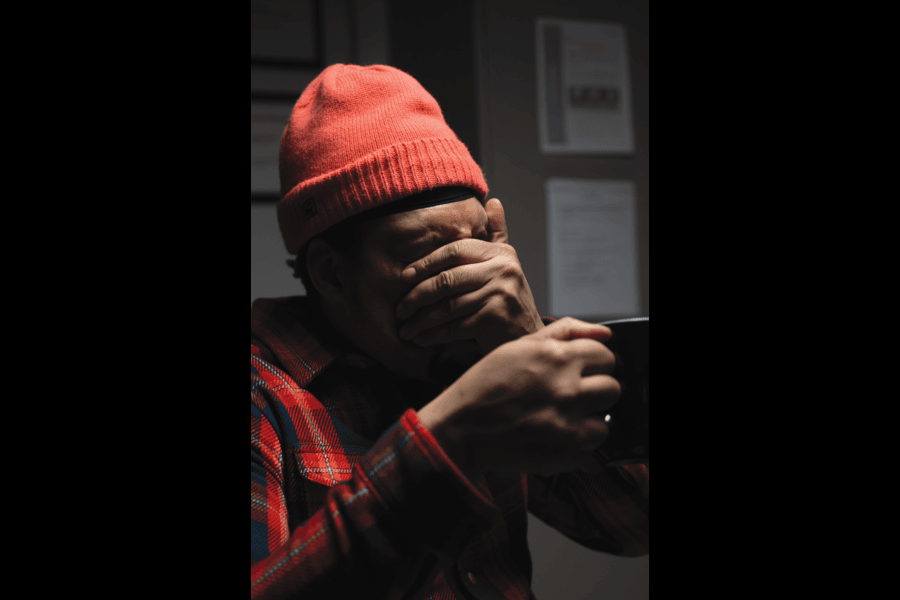

The reaction by wealthy businessmen and politicians in Mexico City is not an outlier in regards to these sorts of proto apocalyptic scenarios. Researchers from Rutgers University, Lee Clark, and Caron Chess call this self-preservation response Elite Panic. Those in positions of power benefit from the collective belief that disaster will bring chaos and mass violence. The idea that humans are one bad day away from destroying each other is manufactured by those who would rather not see us build strong independent communities.

We must begin the great work of imagining a different response to disaster. One that does not prioritize the accumulation of things, but is defined by radically helpful communities that keep each other fed and safe. The world being forecast in Fallout, Mad Max, and the Last of Us do not need to be road maps for some inevitable collapse of society, wherein hope is replaced by fear. Humankind is capable of great good, and somewhere within us we are programmed to take care of each other.

Furthermore, we do not need to wait for a devastating event to begin to take care of each other! The same impulses that would have the public preparing for a brutal collapse of society also work to keep us from collecting our efforts today. Anxieties disguised as self preservation defenses often lead to isolation in our modern world, but we can overcome these barrie