As a younger person who loved video games, I would occasionally be confronted with explaining their appeal. I think that it was easy enough to say “well, they are fun!” and while that may be sufficient for many, some games do not appear fun on the surface. Some games ask the player to take part in repetitive, chore-like tasks, and this genre of simulation-type games is constantly growing in popularity. Such titles like A Little to the Left (a game about moving into a new home), Cooking Mama (a game about preparing dinner) and Farming Simulator (a game that simulates farming) are consistently some of the most popular titles across varied platforms.

I find myself in the shoes of my ancestors wondering what the appeal of these types of games are. These games are essentially work, but I think that the fun comes from the satisfaction of accomplishing a task. I could have never predicted the success of a game called PowerWash Simulator. It doesn’t speak to me at all but I understand its excitement is in the way that it packages the dopamine rush of finishing the dishes or vacuuming the living room without having to do those tasks for real.

While this article doesn’t pretend to tell you that you actually love doing the dishes or folding clothes, I do believe that given the freedom to pursue our interests to our fullest desires we would have a greater appreciation for those tasks that need doing. As people, I don’t think that we are hardwired to hate work, we hate our jobs because they feel meaningless.

In 2013, David Graeber wrote an essay for STRIKE! Magazine that explains this feeling quite well. On The Phenomenon of Bullsh*t Jobs (*added in) asserts that developed countries like the USA should have already been capable of achieving a 15-hour work week. “In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn’t happen. Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless. Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul.“

The essay was translated into 12 languages and produced a genuine response from many in the workplace on the significance of what our jobs entailed. Later, the text was expanded into a full length book which included dozens of testimonials from people with these types of jobs across the globe. One story struck me as it described the routine of a contractor for the German Military who details the layers of paper work he must complete in order to do something as simple as move a copy machine down the hall.

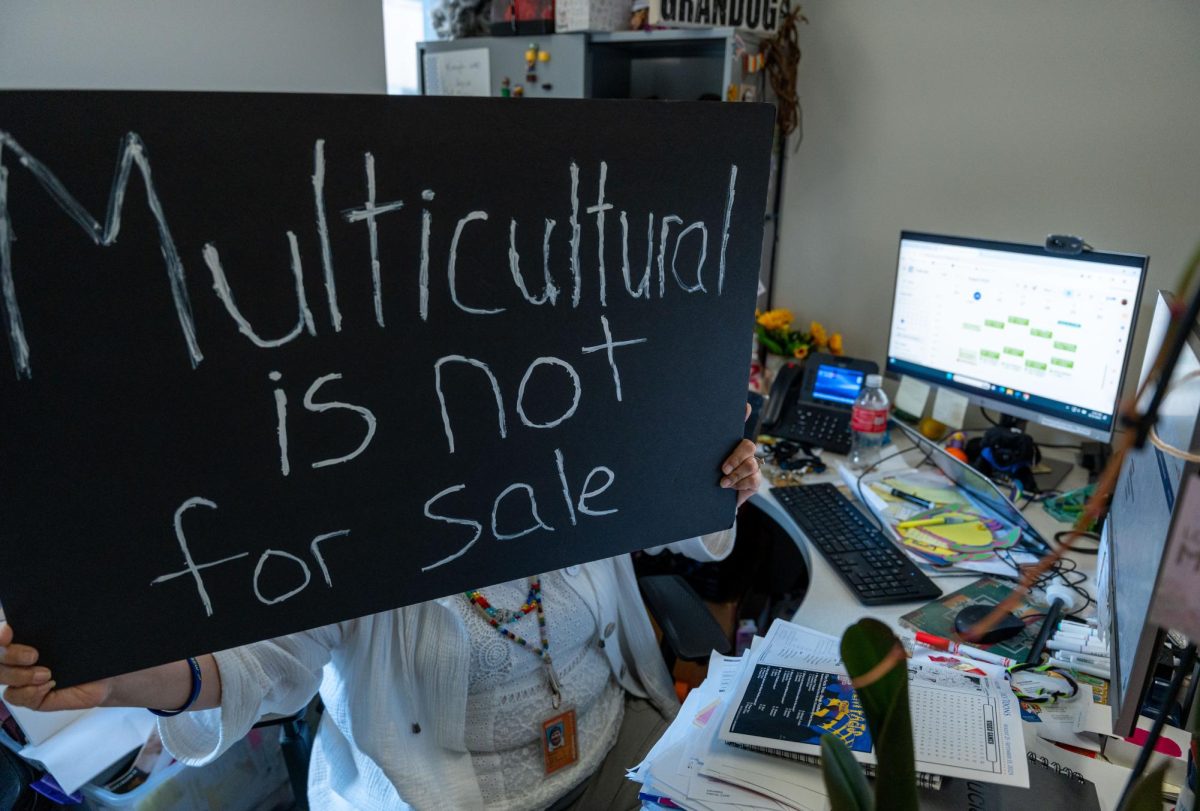

It is interesting to note that this person does not work for the German military, but is rather a private contractor that is hired out by the military. Attitudes towards the efficiency of the private vs public sectors have shifted dramatically since the 1980’s exemplified in the classic quip from Dan Aykroyd in Ghostbusters “I worked in the private sector, they expect results.” However, the stories in this book paint the picture that neither field is entirely free from work that feels pointless.

I read this book years ago and found it compelling to explain attitudes towards the jobs I have worked since I was in high school. In researching this article, I have both reread it and read some of the material responding to it, and I have come to the conclusion that the major hole in Graeber’s theory is that the worth of a job is subjective. Still, I think it provides a challenging perspective on work and our economy at large, and I would recommend the book to anyone interested. In a roundabout way, it also brings us closer to understanding the value of these simulation video games and the desire for meaningful work in and beyond our place of employment.