Back to the Future Day: What the franchise sneakily got right

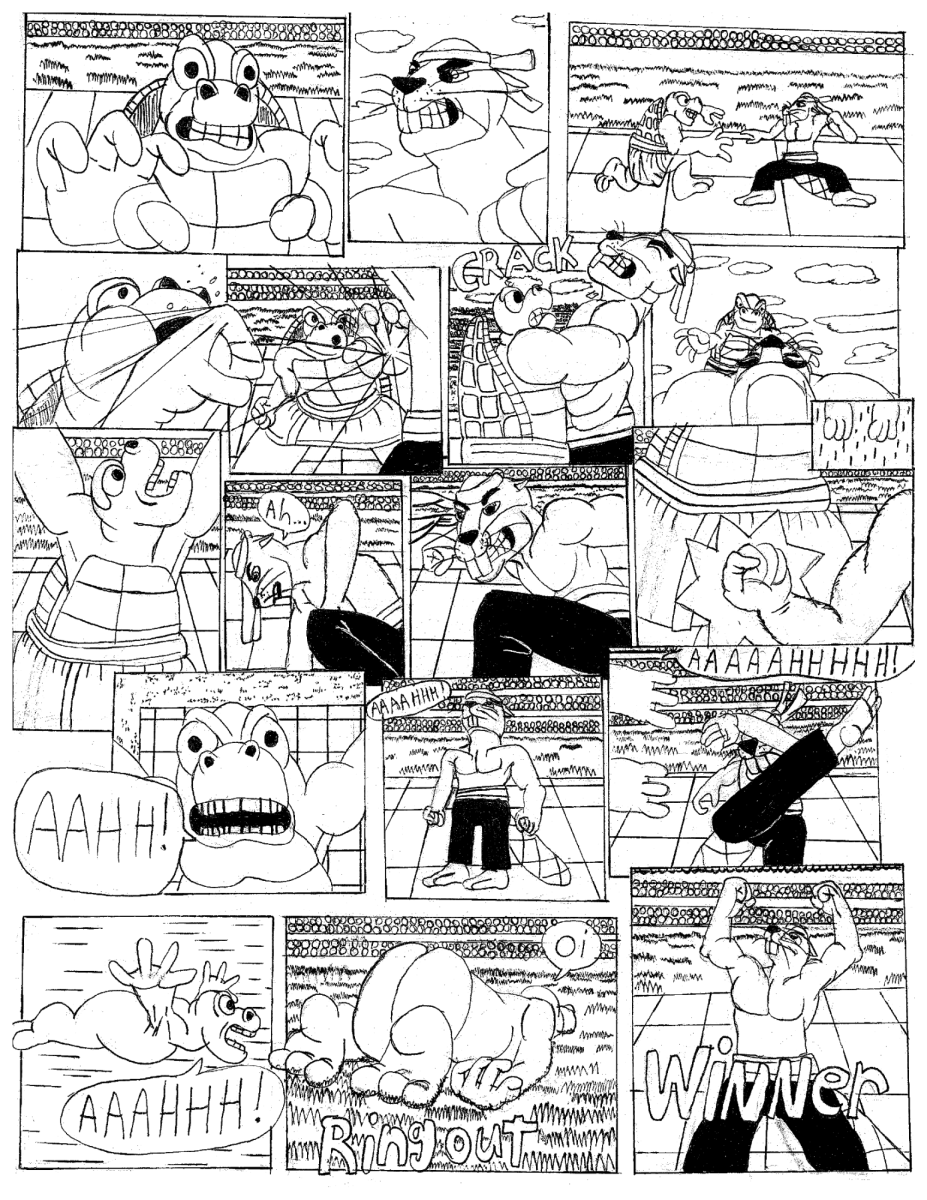

Photo by Tribune News Service

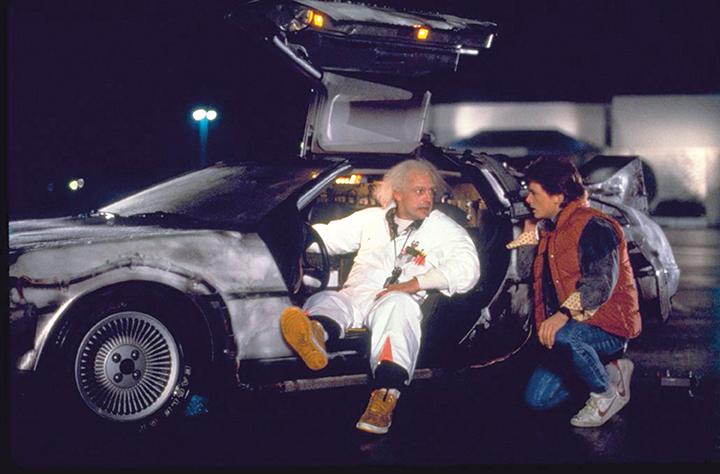

Inventor Emmett “Doc” Brown, played by actor Christopher Lloyd, left, and Marty McFly, played by Michael J. Fox, prepare for the first test of the Doc’s time machine in a shopping mall parking lot in the 1985 film “Back to the Future.” (Photo courtesy Universal Studios/TNS)

Many seismic events have shaken the world in the past 30 years–the fall of Communism, the rise of Clintons and Bushes, the invention of the iPhone, the realization that suspenders are a bad look for anyone under the age of 70.

One constant, however, has been “Back to the Future.” The 1985 Robert Zemeckis teen adventure (and, to a lesser degree, its two sequels) have endured the test of pop-cultural time. A lot of great movie characters come along.

Few remain standing like Michael J. Fox’s desperate-but-wry Marty McFly.

President Ronald Reagan invoked the franchise in his 1986 State of the Union address; Andy Samberg made a reference in the opening of his 2015 Emmy’s speech. Seemingly nothing was lost, or no time had passed in the interim.

At the risk of engendering some elder eye-rolls, “Back to the Future” has become a touchstone for Generation X-ers (and, if a very informal survey is to be believed, for Millennials too) not unlike how “The Graduate” is to baby boomers and “The Best Years of Our Lives” to the WWII generation. Walk into any room of film fans under the age of 45 and reel off the quotes and memes: “Great Scott.” “I’m your density.” The Enchantment Under The Sea dance. “Think McFly, think.” 1.21 Gigawatts. “You’re just too darn loud.” Mention these, and knowing, conspiratorial smiles will follow.

This will also, incidentally, be the only time you can score cool points for citing a Huey Lewis cameo. It doesn’t usually pay to analyze cultural longevity. Some hit movies fade and others stick around. Attempting to understand the underlying factors is about as fruitful as scrutinizing the physics of a flying DeLorean. Yet there are occasions when it might be OK to try.

When it might be worthwhile to decode why some entertainment can be consumed anytime, anywhere, with the same enjoyment as when one first experienced it say, at an upstate New York mall on a summer-camp trip 30 years ago (for example). Movie fans will mark Back to the Future Day Oct. 21, that date, once seemingly so far away, that Marty and Doc land on in the second film. One isn’t typically supposed to deconstruct life’s pleasures.

Yet when I thought about the holiday, and the ways the franchise continues on, with costume parties and cinema showings and concerts–a worldwide live-orchestra tour of the film last week stopped at Radio City Music Hall in New York–I thought about what it meant that it was still around, what it was saying.

And I figured, what the hell? In breaking down the movie’s appeal, there are, of course, the glossy plot elements.

The sci-fi conceit. The multi-generational romances. The ticking clock that has the heroes trying to catch, literally, a bolt of lightning. “You just have a masterfully written script in terms of tightness,” said Alan Silvestri, the film’s composer, who has been touring the world this year with said concert event, when I asked him to explain the movie’s abiding popularity. “Just the way it’s cut, the way it all fits together–it’s exactly right.” (The WGA agrees: in 2006 it ranked “Back to the Future” the 56th best script of all time.) The mix of wholesome and subversive doesn’t hurt either, a point paralleled in the initial Hollywood reaction.

When Zemeckis and co-writer Bob Gale first pitched the idea for “Back to the Future,” they ran into a wall. Some studios thought it wasn’t hard-edged enough for an audience schooled in “Revenge of the Nerds” and “Porky’s.” Then Disney rejected it because its was too hard-edged.

The film also carries with it a playfully obdurate disregard for authority of the youthful sort, with Marty’s guitar-playing lateness in the face of a collar-grabbing principal, and the more adult type, the out-of-the-box science practiced by Doc Brown. Movies about outliers tend to resonate because 90 percent of us think we’re better than average. Few films so skillfully exploit this self-perception better than “Back to the Future.” But there’s something deeper at play, something that both makes the movie creepier on reflection and that could easily have made viewers stop dead in their tracks: the Oedipal element. In watching Marty resist the overtures of Leah Thompson’s Lorraine, we’re experiencing some darkly funny moments.

If the meeting-your-mother were just played for laughs, though, it would amount to little more than a Freudian in-joke. “Back to the Future” does something else: it taps into what we all want to know. “You’re getting to be a fly on the wall when your parents got together, and isn’t that the great fantasy for many of us?” said Gale, when I asked about the film’s enduring appeal. Deep down we all wonder where we came from, how two people very far removed from us came to make a choice that allowed us to even exist and have that thought.

We consider what would have become of us if something so seemingly random hadn’t happened. In “Back to the Future” we can see (as Gale, who came up with the idea of a parental run-in, notes) that process up-close; in fact, we can be participants in it. We can even see the world as our parents did, something we otherwise innately never could. “I think if we didn’t give a chance for people to see that it would have been a nice movie, a nice hit,” Gale said. “But it wouldn’t have lasted.” And then there’s the time travel.

The Oct. 21, 2015, date allows us to play out the events of the movies from out in the audience. In the first two films, Marty first went back and then forward from his own time. It’s a turn 2015 audiences can now mimic. We can return to an earlier era by watching the first movie and recalling how we felt in 1985. Then we can zoom forward by watching the sequel and thinking how our own lives stack up, a trip to an alternate future not unlike the one Marty creates for himself.

That latter phenomenon, and its attendant eerie prophecies and misfired predictions, has grabbed much of our attention on Back to the Future Day. It’s fun to wonder why we don’t have self-lacing sneakers, and what shoe campaigns Nike would come up with if we did.

Of course, fetishizing a future that didn’t happen is exactly what makes the movie fun. One reason “Back to the Future 2” remains enjoyable to watch is because of the ways it depicted a future that seems just out of reach–a look back to a time in which future hoverboards seemed reasonable, as we wonder whether they will indeed ever come to pass. After all, the movie correctly foresaw plenty of other developments– Skype, for one but those seem a lot less exciting.

Either way, many of those “Back to the Future 2” hypotheticals might be beside the point. We may not have hoverboards, no one wears metallic glasses or shiny bespoke outfits (outside of a Daft Punk concert, anyway) and the Chicago Cubs may not be on the verge of winning the World Series (yet).

But the franchise offers us something else: a sense of curiosity. The present foreseen by “Back to the Future 2” may be less important than the ongoing past of “Back to the Future.” Because for all the stonewashed jeans and Van Halen worship (oh yeah, and those suspenders), the 1985 of the movie doesn’t really feel fundamentally different from our modern world; certainly not in terms of attitudes and priorities, and certainly not when comparing it to the 1955-1985 divide and the contrasting attitudes toward sex and feminism. That may be why the franchise stands.

For all the ways it predicts change, it shows that, when it comes to understanding our origins, much remains the same. Mainly, though, it reminds us to be grateful that plutonium isn’t available at every corner drugstore. Yet.